When thinking oneself back into the Age of Mercantile Sail –

which lasted up to WW2 – it is hard to imagine just what a menace was

represented by derelicts – ships abandoned by their crews but still afloat. The

most serious class of derelict consisted of wooden-hulled ships carrying cargos

of wood. Large numbers of such ships were employed on the North Atlantic,

carrying timber from Canada to Europe, and another big lumber trade involved

carrying hardwoods from South America to the Eastern USA through the hurricane-prone

West Indies.

Steel hulls, with their associated heavy machinery are

likely to sink if badly damaged but a wooden hull packed with timber might

border on the unsinkable. In the case of crews abandoning such ships they were

expected to set fire to them. This was however not necessarily done, and if it

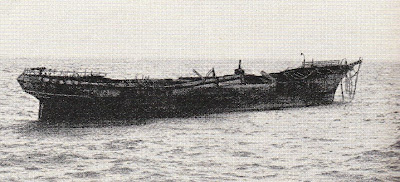

was, it might not be effective. An example is the barque Lysglint, abandoned and set on fire in May 1921, but which only sank

two months later. The photograph shows her as a charred hulk, but still capable

of floating and a massive danger to any ship that might encounter her in

darkness or fog – this being before the days of radar.

Lysglint barque as a derelict in

1921

Such derelicts could drift for very long distances. In 1888 the

schooner W.L.White was abandoned off

Delaware Bay. She drifted for eleven months and her movements were carefully

plotted by the U.S. Hydrographic Department which was studying derelict

movements. She travelled over 5000 miles, driven hither and thither by wind and

current. Reported no less than 45 times

by passing ships, she was finally driven ashore at the island of Lewis, in Scotland’s

Outer Hebrides.

Another long-lived derelict was the Alma Cummings which drifted for 587 days in the North Atlantic after

she had been dismasted and her crew taken off by a passing steamer. Other vessels sent boarding parties no less

than five times but efforts to burn her reduced her upper hull almost to the water’s

edge, making her all but invisible and an even greater hazard. After covering

at least 5000 miles she finally grounded off Panama, her cargo of wood and her

metal fittings being highly prized by those who found her.

The derelict barque Edward L.

Maybury, photographed in the North Atlantic in 1905

The most spectacular derelict voyage was probably that of the

Fannie E. Wolsten, an American

schooner that was estimated to have covered over 10,000 miles in four years,

following her abandonment on the edge of the Gulf Stream in 1891. She was

reported scores of times in the North Atlantic but finally sank off the coast

of New Jersey, not far from where she was originally abandoned.

The scale of the derelict menace was immense. C.D. Sigsbee (1845-1923)

of the US Navy, who was later a Rear Admiral and is perhaps best remembered as

captain of the USS Maine when she

blew up in the harbour of Havana, spent much of his career as a hydrographer. In 1894 he published

a report on "Wrecks and Derelicts of the North Atlantic 1887 through 1893"

which indicated that in this period there were 1,628 derelict vessels adrift

(or lost) in the Atlantic alone.

On both sides of the Atlantic it was agreed that “Something

must be done” and naval vessels were enlisted to tackle the problem. The

solution was not however easy. A timber-filled wooden hull, especially if almost

awash, was not easily sunk by gunfire and torpedoes were considered too

expensive. The only really effective way was to place gun-cotton charges in

such a position as to break the vessel’s back, but gaining access to do so was always

dangerous and often all but impossible. Ships employed by the U.S. Navy for this

purpose included the aged USS Kearsage,

which had sunk the Confederate raider Alabama

during the Civil War but which was now relegated to more humble duties.

Ramming was considered as an option, but this required

sturdily built ships. Though this had fallen out of favour as a battle-tactic

by the 1890s, most naval vessels were constructed with ram-shaped bows. In

practice however derelicts proved tough opponents, capable of giving perhaps

more than they got. The American cruiser USS Atlanta was damaged during such a manoeuvre in 1895, as was Royal

Navy’s protected cruiser HMS Melampus in

1899, both needing to limp home for dockyard repairs.

HMS Melampus, 2nd-class

cruiser, in happier circumstances,

at Kingstown (now Dun Laoighre) in Ireland

An 1896 bureaucratic measure by Britain was to impose a fine

of £5 for failure to report a derelict at the first opportunity. Even allowing

for inflation since then, the sum involved was derisory and the means of

enforcing were limited.

The most

effective measure was finally taken by the Americans who, in 1908, launched the

1445 tons Coast Guard cutter USCGC Seneca,

specifically intended for of locating and destroying abandoned vessels. Heavily

armed for her size and with excellent sea-keeping and towing capabilities she

embarked on a varied 40-year career that also included wartime, ice-patrol, and

rum-runner seizure duties. The photograph

below shows her in action.

USCGC Seneca with a

derelict in tow

The solution to the derelict menace was not however recovery

or sinking – it was time itself. The disappearance of the wooden-hulled merchant

ship, especially those involved in the timber trade, made such hazards rare,

though isolated cases still occur, usually involving much smaller vessels.

Iron/steel hulled vessels have at least the scrap value to make salvage worthwhile. It'd be hard to even cover your costs by selling a wooden derelict as firewood! Most modern navies and air forces would relish such a selection of free practice targets though.

ReplyDeleteI had read in the past on how wooden ships were much harder to sink than one might imagine, but hadn't gone to the next step. Fascinating.

ReplyDeleteWhat a fantastic Voyage this Blog Hop has been! The third part of my Blog Hop article is now up - please do share in this final phase of the Nautical On Line Voyage http://ofhistoryandkings.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/weigh-anchor-nautical-blog-hop.html

ReplyDeleteAnd...

Thank you to all who participated, authors and visitors alike. The Voyage has been wonderful!

Tanks for the post, I think I always thought that an abandoned ships would sunk quickly.

ReplyDeleteFallen containers are now a similar problem for sailing boats.